Leadership: you can have good leadership (no recent example in education comes to mind) and bad leadership (Hekia Parata) and no leadership (Chris Hipkins) – which constitutes an abdication to bad leadership

The way the present dominant education philosophy is almost impenetrable to historical experience

The passivity to a foreign philosophy introduced through the Treasury via a prime minister in his sherry stage

The passivity to history as if we were living through it in the present

Our repugnance to the idea that life is chancy, preferring to see it as pretty much inevitable, therefore better to just go with the flow

The rejection by the left to the idea of leadership, of the left preferring to see history as inevitable instead of seeing it as that which needn’t have been

To the way the right in leadership just has to fall back on neoliberalism for its concepts but the left, with no such easy resort, has to come up with its own concepts – which it lacks the will or confidence to undertake

The availability of a concept which is the answer to the leftist dilemma – it is called democracy – imagine a truly democratic education system, but we need leadership to take us there

What the main aim for school education in a democracy should be: Preparing children for life in a democracy and to support and protect it

That main aim should then guide all decisions

The way such a main aim would help to provide a balanced approach to technology and the humanities and the arts

The curriculum and teachers and children being at the centre (oh wow! if this was true how chasmically different things would be from the shambles unfolding)

Reducing bureaucratic control

The need for more teacher curriculum freedom

Removing constant fear, heavy-handed constraint, and playing it safe when teachers make choices about what and how they teach, and how they evaluate

The need for external supervision being mainly advisory, also accountable

Principals knowing the real curriculum

The absolute need for Maori language to be introduced to all schools in a timely manner

There being no such thing as 21st century education, just a struggle for ideological control of the present

National standards not being worth the paper they are written on

NCEA, unless an exam, being very suspect

The way the corruption of national standards means signals are not being sent about the low achievement of children at primary

The way the corruption of NCEA means signals are not being sent about the low achievement of children coming from primary – yes, I mean primary – children are too far beyond the education 8-ball when they arrive at secondary

The way the corruption of NCEA means signals are not being sent about the failure of NCEA to lift achievement

The way pressures on universities to maintain enrolments means signals are not being sent about the low achievement of students coming from secondary

Gold standard research that shows that only 20%-30% achievement is attributable to schools

Teacher training not being about the real curriculum (a semi-independent institution is needed)

The need to increase intellectual challenge by making learning more affectively involving

Recognising that schools are not businesses meaning BOTs and principals need to have their role fundamentally modified

The need to debunk evidence-based learning

Teacher knowledge which should be up there with all other knowledges such as academic and bureaucratic

The need for an advisory service free from financial and ideological pressures.  The cycle of misunderstanding and mistreating of primary education about to recur

The cycle of misunderstanding and mistreating of primary education about to recur

Primary education is curriculum-based and fiercely knowledge fought-over and, if anyone had the courage to truly test and examine it, would find it broken. Secondary is limping along: mainly because primary school children arrive without sufficient coherent knowledge and motivation. And universities, under enrolment pressure to keep numbers up, fume but are chary of being direct.

On the whole, secondary education was left largely untouched by Tomorrow’s Schools and its prolonged aftermath, protected as it was by its examination-based curriculum (the knowledge therefore being far more settled); by the bureaucrats and politicians who understood secondary education better and took it more seriously so were loath to take risks with it; by the public which saw secondary as bearing more directly and sensitively on the futures of their children; and by its departmental structure, the size of the schools, more informed and energetic teachers organisation, and by far more of the bureaucrats and decision-makers involved in Tomorrow’s Schools coming from secondary.

Primary education in New Zealand receives 33 per cent of the OECD average, secondary education the OECD average. A gap that has appeared and widened in the Tomorrow’s Schools’ period.

The system combined to break primary, largely because it was viewed as a kind of junior version of secondary, and so, under the bureaucratic headings of administration, organisation, and governance, the two were treated the same, but the burden, as described above, was applied and fell, very differently – and, is about to happen again, slightly different in process, but the same in outcome.

The consultation will be with principals who are the beneficiaries of the national standards administration, organisation, and governance changes; and with teachers who have never known anything else.

To understand primary you need to understand the curriculum, the real curriculum, and based on the real curriculum, develop structures which sustain it.

Early childhood was protected by its iconic and beautiful curriculum, Te Whariki, and that by its strong women both in the universities and in the system who guarded it like maternal warriors. They also fended off quantitative academics, politicians, and bureaucrats (note the beginning of knowledge wars, though, begun in the Listener by John Hattie and Ken Blaiklock, supported by Hekia Parata). Anyway, delving and experimenting with education policy in early childhood was not so emotionally, ideologically, and politically gratifying as doing so with primary school children.

The neoliberalism of the Treasury found its scope in primary and its instrument in David Lange to put primary education to the sword.

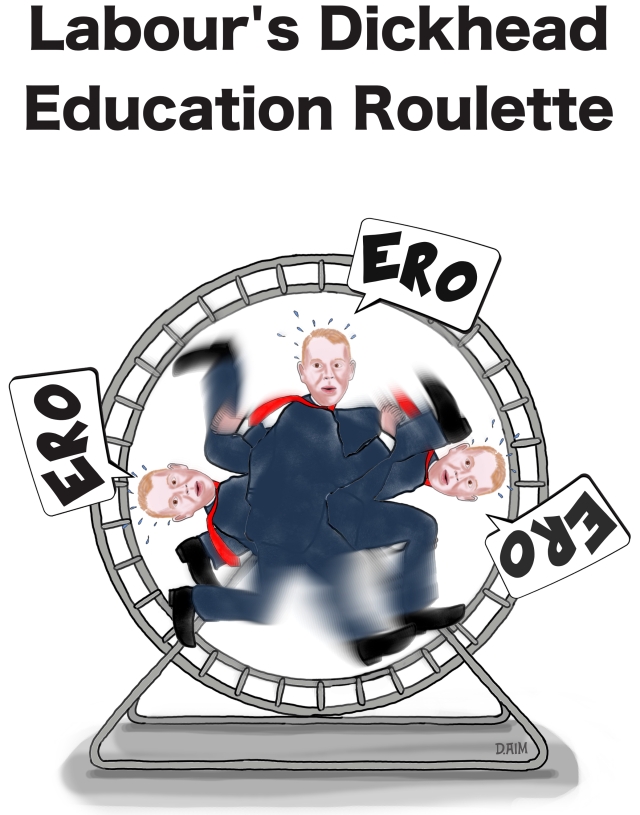

Labour has been little better than National, but Labour, in being the originator of the primary school neoliberal education tragedy labelled Tomorrow’s Schools – meant primary school teachers and children were stripped of their natural political ally and left bereft and isolated.

Tomorrow’s Schools was directly aimed at primary schools and it shows, one of the many pointers being the poor performance in the latest international tests when, at the beginning of Tomorrows Schools they were at or near the top. It is with primary education that politicians of both parties have played their games. The especial tragedy is that the primary school system, in comparison with other education systems, as a result of the education truths established by Clarence Beeby and Peter Fraser, had been the jewel in New Zealand’s education crown.

And so the cycle of misunderstanding and mistreating of primary education is about to recur to the devastation, a kind of silent devastation (because who has truly shown they have cared enough to pursue the truth no matter what), of another generation of children.

Written in 1988 as I prepared to resign as a senior inspector of schools to go out on the road to mitigate the worst effects of the education harm that were bound to beset primary education

Written in 1988 as I prepared to resign as a senior inspector of schools to go out on the road to mitigate the worst effects of the education harm that were bound to beset primary education

1. For a democratic, participatory education system, production and validation of knowledge should be shared amongst a number of groups. One of the reasons why New Zealand primary school classrooms function as well as they have is because of the checks and balances inherent in the system. Those checks and balances derive from the relative co-operativeness in the way groups relate to one another. No group can carry out its functions without the support of a number of others, and no group can force its will on another. Ultimately, though, it must be acknowledged that what the government wants, the government gets, but what the government wants can be modified by those outside the government educating the public to influence the government – success in this being the measure of teacher organisations. In the absence of the inevitable conflict and control behaviours generated by a strict hierarchical system, these groups have been able to remain mindful of the need to negotiate in a spirit of goodwill to be able to proceed.

2. But that democratic, participatory education system, under the hold of positivism, is at risk. In a national education system, to argue against a substantial exertion of hierarchical control is a contradiction in terms. But because bureaucratic control begets bureaucratic control, a democratic education system needs a strong dispersal of power to schools and classrooms to help establish a finely graded system of checks and balances. It may not result in a system that meets the highest standards of efficiency for, say, an industrial product but is, it is suggested, the most efficient way for administering value-laden education systems. A paradox becomes apparent: reduced orthodox hierarchical efficiency can lead to enhanced pedagogical effectiveness.

3. Teachers are unsettled by the possibility of curriculum and administrative ideas being able to be passed quickly down the hierarchical chain without those ideas requiring teacher involvement at all stages of development. The best ideas for education come from teachers and those close to teachers. The part of the education system that is important to teachers is the part close to them. The part further away has the capacity to do much harm, but little capacity to do much good. The nature of the education system should protect teachers from hastily conceived ideas – no matter their potential benefits. Good ideas are only good if the process for their development has been good. The last thing teachers want is the kind of efficiency that has someone in the hierarchy having an idea and then using the chain of command to force it on them.

4. So we are talking about a collaborative education system. Collaboration occurs in system and institutional relationships when the opportunity for dominance is structurally reduced. It is not talking about collaboration to bring about collaboration. Indeed, the more conflict inherent in structures, the more collaboration, as a cover, is likely to feature in the talking. Collaboration only occurs over the long term when the structural realities encourage and enable it.

5. If teachers continue to be in a position of disadvantage in relation to knowledge, then they will continue to be at a disadvantage organisationally within the system. That is not good for teachers and children. What is the good of every other adult group in the system – including principals who identify more with the hierarchy – having a great time, when it is teachers who, in the end, deliver the goods?

6. As I prepare to travel around New Zealand campaigning for the holistic and democratic as against the positivist and hierarchical – where does this leave my message?

7. The neoliberal education arguments are not really about education but about the movement of power to the centre to impose laissez faire capitalist beliefs, with education a particular focus as a way to take control of the future and stifle education as a source of alternative ideas. In response, I intend to talk and write about a holistic education system, democratic values, and the importance of genuine power sharing and social equity. We can, as referred to, only get the kind of education system we want if there is the social context to match, so I will talk and write about that. And the kind of education system we should want is a holistic one built on variety, collaboration, and stretching children imaginatively and creatively. Politicians, bureaucrats, and academics tend to fear and reject the holistic because the dynamic and humanistic main aims characteristic of the holistic make all of the component parts of teaching and learning fall into place serving to give power to teachers. Politicians, bureaucrats, and academics, on the other hand, are fixated on complex arrays of objectives that can be measured and, in practice, often work against each other to intended subversive and control ends. It is about control: the holistic gives power to schools and teachers to work things through to children’s advantage; objectives with their fragmentation and measurement give power to politicians, bureaucrats, and academics to work things through to their own.

Considering the harshness of the current power structures and the self-serving arguments they are based on, I don’t expect the holistic and the democratic message to succeed in my time, but time, in the end wins, nothing is forever, events turn and crises come, and change becomes irresistible, change which can be for the better or the worse, who knows, so the idea is to get the message out there, it might be the time for all who have fought for a kinder, fairer society, and an education system to match, for their time to come. It is that which spurs me on.

Kelvin Smythe

1988

Should you have any time in your schedule, visit us at A.G.E. The holistic, democratic vision supporting curious, caring and creative children, may well inspire educational change.